Published: 2025-06-09

A conference on May 27, 2025, addressed the shifting dynamics of health communication, health misinformation, trust, and health care practices in the era of Artificial Intelligence and digital transformation.

The event, titled “Health Communication in the Digital Era: Information, Trust, and Strategies” brought together leading scholars and industry practitioners in the fields of communication and healthcare to foster cross-disciplinary collaboration.

It was organised by Hong Kong Baptist University’s Department of Communication Studies, in collaboration with the Centre for Media and Communication Research (CMCR) and HKBU Fact Check.

|

Stephanie Tsang speaking at the conference |

“We are excited to team up with local fact-checkers in Hong Kong for the purpose of bridging the gap between academic research and real-world application”, said Stephanie Tsang, Assistant Professor in HKBU’s Department of Communication Studies and the convener of the event, “Our goal is to equip industry stakeholders with effective healthcare communication strategies while offering researchers fresh perspectives from the field”.

In her welcome address, Regina Chen, Professor and Head of the Department of Communication Studies emphasized the need to comprehensively explore new ways to stem the tide of harmful infodemic and develop better communicative strategies to share accurate health information. “The conference is expected to make a significant impact by providing actionable solutions that resonate beyond academia, shaping more effective and trustworthy health communication practices for the future,” she remarked.

|

Regina Chen speaking at the conference |

Navigating Human and Technology-Driven Health Translations in the AI Era

In healthcare settings, accurate information can mean the difference between proper treatment and medical error as misinterpretations of information can significantly impact the delivery and quality of care. Yet, language barriers often force patients and providers to rely on translators.

Elaine Hsieh, Professor at the University of Minnesota, noted that while interpreters have traditionally served as vital conduits for conveying health information across cultures, the rise of technology-driven translation models is reshaping how interpretation functions within cross-cultural healthcare settings. In her presentation titled “The Role of Technology in Healthcare Interpreting and Culturally-Tailored Communication Strategies”, Hsieh drew on the Bilingual Health Care (BHC) model to highlight the different structural, linguistic, and emotional needs that both human interpreters and technology-based interpreters like; voice assistants, Google translate, Live translations, among others, provide in health care settings.

While AI-assisted interpretation can enhance clinical accuracy, Hsieh emphasized that such technologies fall short in delivering the emotional and relational aspects essential to effective healthcare communication. She highlighted the absence of trust-building, relationship development, uncertainty management, and emotional support in technology-mediated interpretations. Furthermore, she pointed out that these tools often lack cultural competence and contextual sensitivity. “Interpreting is more than textual accuracy,” she stated.

|

Anthony Pym (virtual attendee) speaking at the conference |

Building on this theme, Anthony Pym, Professor at the Universitat Rovira i Virgili, questioned whether healthcare providers and patients should place their trust in digital translation technologies. In his keynote speech titled “Trust in Digital Health Communication”, Pym explored the concepts of “thick” and “thin” trust towards the various language translators within the context of intercultural communication in healthcare.

He explained that thick trust is typically reserved for close family members, whose roles often extend beyond language support to providing emotional reassurance and a sense of familiarity, elements that are especially crucial in high-stakes medical situations. In contrast, thin trust is associated with certified professional interpreters, whose primary allegiance tends to lie with the medical institution rather than the patient. However, Pym noted that in the absence of trust in human mediators, technology-assisted translations can still attract a certain level of trust. “In such cases, the trust people place in these tools is neither thick nor thin,” he explained, “but rather exists at a low, vigilant level.”

|

Elaine Hsieh (L) and Eric Kramer (R) (virtual attendees) speaking at the conference |

Eric Kramer, Professor at the University of Minnesota, explored the interplay of power, knowledge, and politics in an increasingly technologized world and the transformative impact of digital technologies. He asserted that digital accessibility has intensified power imbalances, fostering alienation and disconnection. As a result, disparities in health information persist as a significant existential challenge.

Diffusion of Health Misinformation on Social Media

In today’s digital age, where information is abundant and often conflicting, discerning credible health information from misinformation has become increasingly challenging, hindering informed health decision-making. In his presentation on the role of social media in the spread of fake news, Edson Tandoc, Professor at Nanyang Technological University, noted that individuals who primarily rely on social media for information are more vulnerable to health misinformation and struggle to identify false news compared to people who rely on traditional media as sources of information.

|

Edson Tandoc (virtual attendee) speaking at the conference |

Tandoc argued that most social media users tend to passively receive information rather than actively seeking it out. “By embracing a ‘news-find-me’ approach to information consumption, media users become less inclined to critically evaluate or verify the content that reaches them,” he remarked. He also identified socio-cultural factors such as cultural beliefs, respect for authority, and collectivist values as key drivers of health misinformation. Tandoc noted that deep reverence for authority figures can create hesitancy in correcting false information they disseminate, further perpetuating misinformation.

|

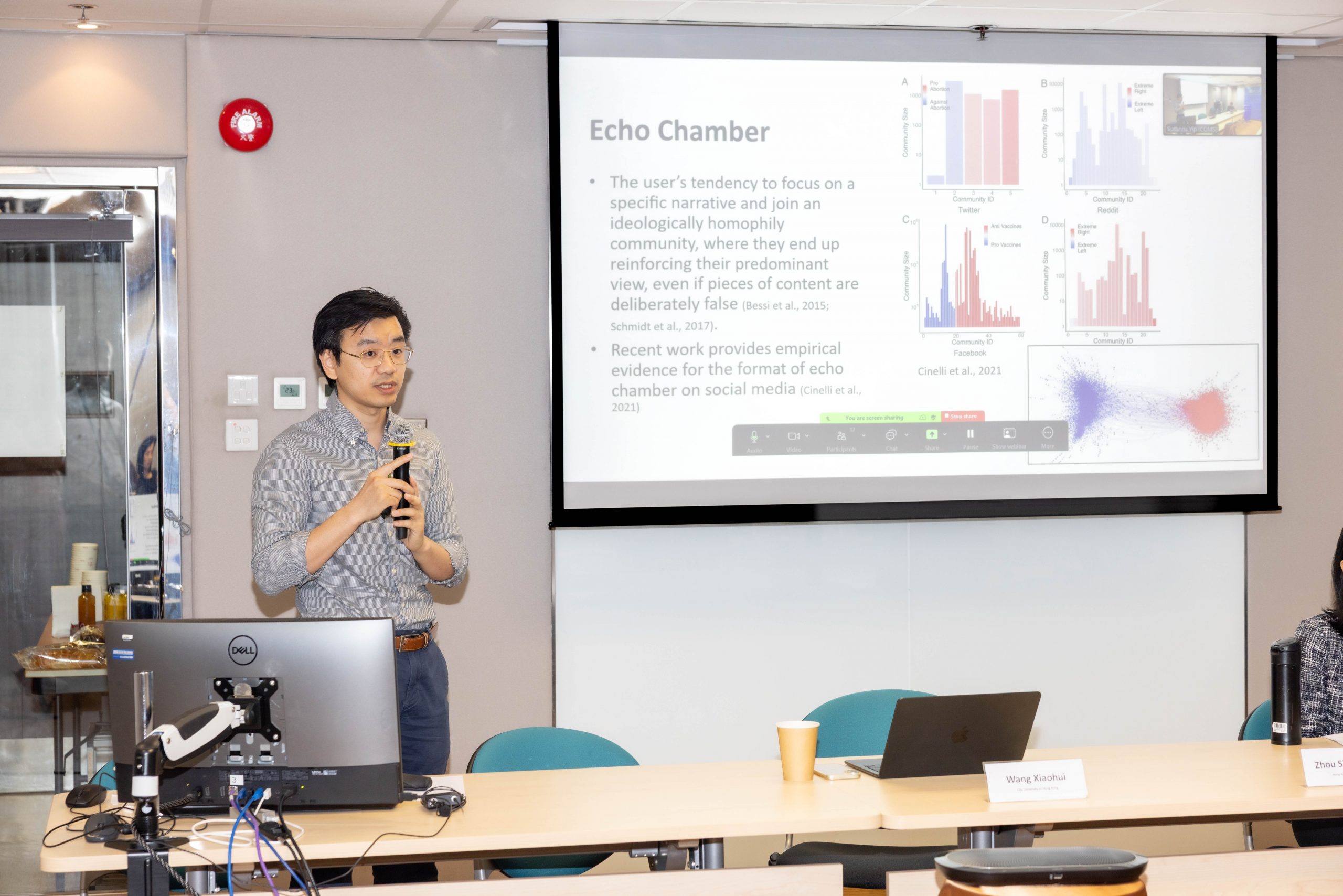

Xiaohui Wang speaking at the conference |

Xiaohui Wang, Professor at City University of Hong Kong, expanded on this idea by examining the influence of network structures and echo chambers in the spread of health misinformation in his talk titled “The Dynamics and Diffusion of Unverified Health Information”. Wang presented empirical evidence demonstrating that prevention-related misinformation often spreads faster than accurate information. He further noted that individuals who share similar ideologies and rely on the same online communities for news are more prone to perpetuating misinformation.

|

Vivien Zhou speaking at the conference |

Vivien Zhou, Associate Professor in HKBU’s Department of Communication Studies, analysed this phenomenon through an embodied perspective. In her presentation, titled “Embodied Experience and Self-Verification in Health Communication”, she examined how embodied experiences, shaped by power, culture, gender roles, and self-awareness, contribute to the understanding of health information. Zhou contended that health communication extends beyond mere message transmission to include embodied processes, which she outlined in four key layers: self-discovery and identity construction, personal growth and development, the integration of healthcare practices and terminology into daily life, and holistic transformation reinforced by communal support.

Industry Perspectives on Fact-Checking Health Misinformation

Another highlight of the conference was the roundtable discussion where six industry experts, Purple Romero and Sophia Xu (Agency France Presse), Kayue Cheng (Fact Check Lab), Cherry Lai and Masato Kajimoto (Hong Kong University (HKU) Annie Lab), and Lin Zhou (HKBU Fact Check) explored strategies to combat misinformation, enhance trust, and improve communication methods to ensure the public receives accurate and reliable health information.

|

(L-R): Kayue Cheng, Purple Romero, Cherry Lai, Masato Kajimoto, Sophia Xu, and Lin Zhou |

Romero observed that health misinformation, particularly deceptive weight loss products, thrives on people’s fundamental desire to survive and maintain good health. She further noted that emerging technologies, such as AI and deep-fake videos, are increasingly fueling the creation and dissemination of harmful health misinformation using hyper-realistic videos and altered images. As these technologies advance, verifying false claims has become increasingly challenging as they appear accurate and believable. “Unfortunately, health misinformation is something people believe more than actual experts,” Romero remarked “But what AFP has been doing to combat these kinds of false information is to offer health courses online to keep people well-informed”.

Lai identified the misunderstanding and misrepresentation of scientific information as a key factor in the spread of fake news. She argued that scientists and medical experts primarily publish their research for their peers in the scientific community, rather than for broader public understanding. As a result, decoding complex medical jargon often leads to the misinterpretation of vital health information. Cheng further supported this idea, noting that the public is often exposed to health misinformation from journalists, health websites, and scientific journals that appear credible on the surface but may, in fact, be misleading.

Lai pointed out that scientific journals can sometimes contribute to misinformation and suggested that experts should provide clear, accessible summaries alongside their research to prevent misinterpretation by the general public. Kajimoto reinforced this idea, stressing the importance of training medical students to fact-check and verify health information before disseminating it. He further emphasized that, beyond educating journalists on how to fact-check medical science, it is equally essential to equip medical scientists with an understanding of how misinformation spreads due to misinterpreted medical data and how to communicate their findings effectively to the public.

These valuable insights shared by researchers and industry experts enhanced public understanding of health issues and fostered better outcomes through stronger, evidence-based communication. The solutions presented at the conference extend beyond academia to influence the development of more effective and trustworthy health communication practices for the future.

|

Participants at the conference |